A UN-backed force is finally being sent to try and restore calm to Haiti, but experts fear it may have no more success than previous foreign interventions in an impoverished nation hit by crisis after crisis.

Haitian officials have pleaded for a year for help in battling armed gangs ravaging the Caribbean nation -- just one of the challenges facing the poorest country in the Americas, whose political, economic and public health systems are also in tatters.

The multinational mission, which will be led by Kenya, "could be a relief" for people in cities such as the violence-plagued capital Port-au-Prince, noted Robert Fatton, a Haiti expert at the University of Virginia.

But "I'm somewhat skeptical about the ultimate success of the mission," he told AFP. "Anything that is short term, if you don't resolve the political issues, will obviously collapse."

On Monday the UN Security Council greenlit the Kenyan-led multinational mission -- not officially a United Nations force -- which could take months yet to deploy to Haiti.

Nairobi has promised 1,000 police officers, but details are still not finalized -- including the total number of boots on the ground.

One figure that crops up often is 2,000 -- a "limited force" when facing the possibility of guerilla warfare on an urban battlefield in a foreign country, Fatton pointed out.

The United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (Minustah), which deployed from 2004 to 2017, counted some 10,000 Blue Helmets at its peak.

The progress it made towards ridding Port-au-Prince of gangs was wiped out by the devastating 2010 earthquake that killed some 200,000 people, ushering in a new era of instability.

Minustah never won the trust of Haiti's people, its image tarnished by accusations of sexual abuse as well as a cholera epidemic -- brought in by Nepalese peacekeepers -- that killed some 10,000 Haitians.

Since then, gangs have flourished -- murdering, kidnapping, and recruiting young Haitians with no prospects as the former French slave colony struggles to get back on its feet.

Whether Kenyan police will be a match for Haitian gangs on their own turf is doubtful, says Emiliano Kipkorir Tonui, who has overseen the deployment of Kenyan troops in several countries.

"Our policemen are not trained like the military in map reading. They are not trained in communication. They are not trained in handling weapons like machine guns," the former soldier, now a member of the Nairobi-based NGO Kenya Veterans for Peace, told AFP.

And that's before you consider the language and cultural barriers.

The force will need "Creole-speaking advisers who can help them engage the public," warned Richard Gowan of the International Crisis Group -- a challenge in itself, given the experience Haitians have had with previous interventions such as Minustah.

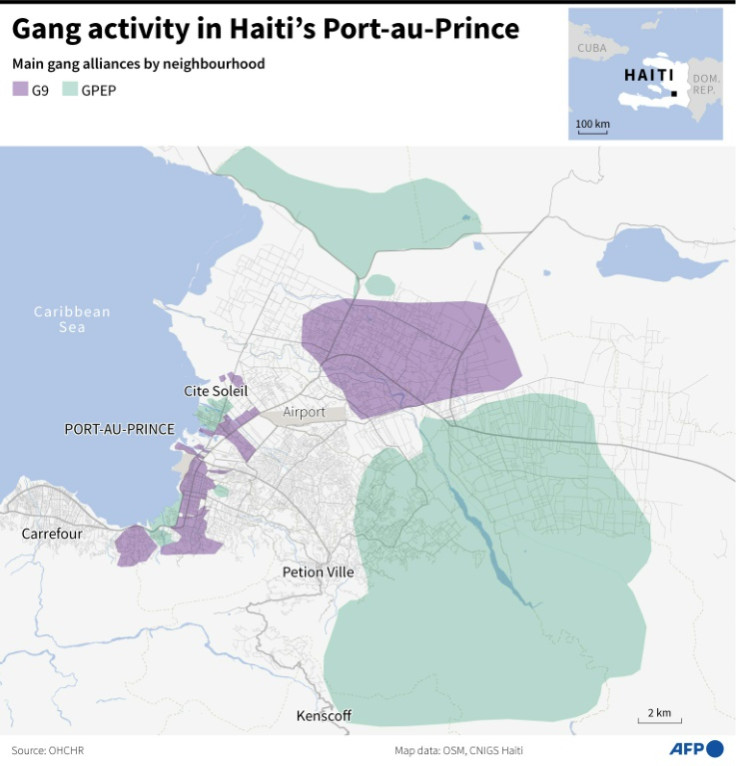

One huge hurdle will be "getting detailed intelligence on gang networks," Gowan added.

Accusations of violence by the Kenyan police are unlikely to help, human rights activists have pointed out.

The Security Council resolution stresses strict compliance with international law and human rights, and the US ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield has said the mission must "learn from past mistakes."

That includes leaving too quickly.

"It's a long game," Stephane Dujarric, spokesman for UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, has stressed.

No elections have been held since 2016 and the legitimacy of Prime Minister Ariel Henry, appointed by the last president Jovenel Moise just before his assassination in 2021, has long been controversial.

Experts insist the mission must be accompanied by an inclusive political process leading to free elections.

But Haiti's political opposition groups are wary, said Fatton.

"I think many people fear that if those troops do get to Haiti that this will solidify the grip on power by Ariel Henry," he said.

Still, there is room for optimism, argues Keith Mines of the US Institute for Peace, who warned the reluctant international community against seeing Haiti as a "lost cause."

In the last two decades alone Haiti has seen the ousting of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 2004, the wreckage of the 2010 quake, the cholera epidemic and Moise's assassination -- and that's before you even dive in to its longer history of French colonization, the slave trade and revolution.

"It's kind of been one bad thing after another," Mines said. "There's some bad assumptions, an unhelpful understanding of what hasn't worked and what has worked.

"I think that's misguided," he said. Between the blows of fate, "there has been a lot of progress at different times."