Establishing voting districts is an intrinsic part of political geography and an ongoing chore in American representative democracy. In the U.S. a national population census determines how many voting districts each state gets. Every time a census is taken, a state’s map of congressional districts might have to be reshuffled. That process has been a partisan s***show for as long as we can remember. In 1812 Massachusetts Gov. Elbridge Gerry passed a redistricting law that would help his party. The plan included a new and highly abstract district that slithered around the map like a salamander. Denouncing the geographical abhorration, an opposition newspaper printed a cartoon of the long, crawling district and labeling the new political species a “gerrymander.”

The practice of “gerrymandering” has been with us ever since, though recent efforts by citizen referendums have began to curb the power of career or partisan politicians. For years dominant parties led by modern Gerrys have used their power to consolidate power. So what is gerrymandering and how does it work? Voters often group geographically in ways that reflect their politics. Once pollsters and geographers look at how people vote and where from, they can shape maps to group all of their opponents together or split them apart, depending on how it helps their own partisan agenda. The Washington Post does a great job of explaining this visually. A Vox explainer shows a glaring example of the end results. For example, it cites a voting shift in 2012 following a redistricting plan passed by Republicans in Pennsylvania in 2010.

“Though House Republicans won only 49 percent of Pennsylvania's popular vote, they won 72 percent of its House seats. And in 2014, the party breakdown of the state's House seats stayed exactly the same,” Vox explains.

A new set of voter initiatives and legal rulings might be changing that. Voter initiatives in states like California, Florida and Arizona have demanded that politicians map out districts in a less partisan way, or pass the work off to independent commissions. On Thursday, the Florida Supreme Court confirmed the power of such initiatives: it ordered a less partisan redistricting. In June, the Supreme Court affirmed Arizona voters’ rights to form an independent commission, saying that the voting public were essentially part of the state legislature (which, according to the U.S. constitution, is tasked with defining districts).

“The people of Arizona turned to the initiative to curb the practice of gerrymandering and, thereby, to ensure that Members of Congress would have ‘an habitual recollection of their dependence on the people,’” Justice Ginsburg wrote in the majority opinion, quoting the Federalist Papers.

How Republicans ‘Stopped Caring’ About Latinos?

There’s no independent commission in Texas, where partisan redistricting is a vicious political tradition. In the 1990s, Democrats drew out districts that packed suburban Republicans into a few slithery gerrymanders. It made those areas very safe for Republican candidates but reduced the number of viable candidates. In 2003, Republicans came to power and did the same thing (fun fact, Democrats fled to New Mexico to try to prevent Republicans from reaching a quorum).

The victims in this partisan tug of war were Latino voters, writes Slate’s Boer Deng, who speculates as to why Republicans “gave up on Hispanic voters” in 2012.

“The parlor game of making districts into shapes that belong on a Rorschach test to guarantee safe seats means Republican candidates often have few Hispanics they need to bother to please. So if you are say, David Brat, with only the objective of winning this year’s nomination for Virginia’s 7th District, the pragmatic approach is to run on short-term appeal to a white, activist, and generally older electorate that doesn’t like, or doesn’t care about, immigration,” Deng writes.

How Democrats Helped A Latino Candidate (And Splintered The Vietnamese Vote)

Gerrymandering is a bipartisan problem, perpetuated not by party ideals but a desire to stay in power. The problem of redistricting cuts across racial lines. It can both help and hurt minorities. Break an ethnic group up among too many districts and they’re unlikely to be able to elect someone from their group. Bundle a group together, and much of their vote become superfluous, “wasted” on one candidate when they could have been a factor in multiple races.

“[We] reconstructed the Democrats’ stealth success in California, drawing on internal memos, emails, interviews with participants and map analysis. What emerges is a portrait of skilled political professionals armed with modern mapping software and detailed voter information who managed to replicate the results of the smoked-filled rooms of old.” Olga Pierce and Jeff Larson and wrote in a details piece for investigative journalist outlet ProPublica in 2011, for a piece called “How Democrats Fooled California’s Redistricting Commission.”

The piece took a shot a Congresswoman Loretta Sanchez (D-California) whose close supporters reportedly lobbied to get her a safe district. In order to do that they reportedly argued for a more Hispanic congressional district at the cost of splintering two neighboring Vietnamese communities. One was a friend, the other a former staffer. It’s not clear if Sanchez encouraged or advised them. As Pierce and Larson revealed, Sanchez’ supporters didn’t disclose their relationships with the legislator. The result? A safe Latino district for Loretta and -- according to ProPublica -- a dilution of the Vietnamese vote.

Double-Edged Electoral Sword

One could argue that lumping Latinos together helps unite them. It probably results in more Latinos getting elected to office. Sanchez’ first election was won by a few hundred votes. After redistricting, which bumped up the percentage of Hispanic voters, she won between 62 percent and 69 percent of the vote in subsequent years. If ProPublica’s article is right, that could be seen as a pro-latino power grab that helped strengthen a future senate candidate (Sanchez has declared her run for 2016).

However, not all safe districts are created by the politicians who benefit from them directly. African American Congresswoman Corrine Brown (D-Florida) has won similar margins in the Sunshine State’s 5th district, which was identified by the Florida Supreme Court ruling as a clear gerrymander; it even looks like a reptile on the map. She certainly didn’t ask Republicans to make it easy for her. Yet they they carved out districts in a way that would dump even more liberals into areas that Brown would clearly win. That upped her margin of victory but made it easier for Republicans on bordering districts.

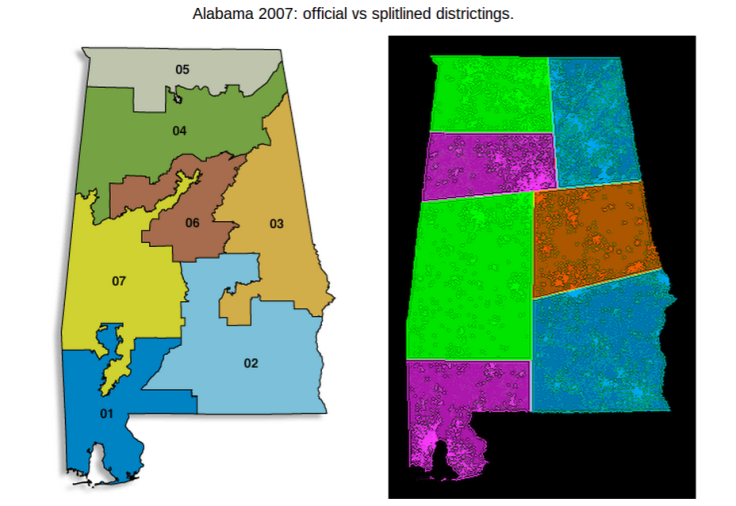

The only constitutional requirement that states face is to make sure that voting districts represent relatively similar populations. Everything else is politics, argues RangeVoting.org, a voter advocacy group. In an objective world, they say, congressional districts would split up populations abstractly. Districts could ignore geography, history, and ethnicity all together (as on the right below) and be determined by an algorithm. The current model (on the left) is slightly more practical (it probably skirts along existing municipal or county boundaries).

Those kinds of algorithmic state divisions might not be practical, but they demonstrate that redistricting can be done in different and less partisan ways. The good news is that from Arizona to Florida that’s already happening. While state redistricting committees can be manipulated (as in California), the recent decisions of federal and state courts confirm that we can improve on the old partisan model.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.