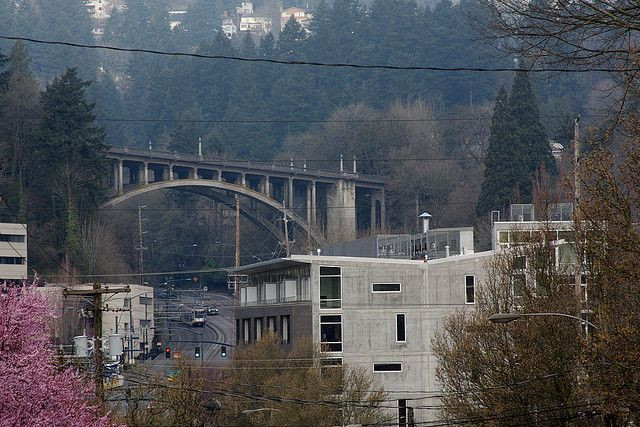

Attorney Kenneth Kahn shares an office with his wife almost directly under the Vista Bridge, a serene gray arch of a structure that is ensnared with trees and an iconic sight along the Portland landscape. Despite its looks, it has a chilling reputation for being casually refered to as "The Suicide Bridge." It's no exaggeration. Kahn has heard the horrid sound of bodies falling within earshot of his office. He's discovered the remains of eight people.

"Just imagine a human being detonating," he said.

Kahn has since spearheaded a group, Friends of The Vista Bridge, as a means of suicide prevention, especially by jumping off the bridge, in Portland, the Associated Press reported. Its mission is to set up barriers to deter jumpers, a measure taken by cities across the country -- and the world -- with a suicide problem, from old Spring Canyon Bridge in Santa Barbara, Calif. to El Viaducto de Segovia in Madrid. The group believes a barrier could halt those intending to kill themselves as a sucide by jumping tends to be impulsive by nature, an impulse a barrier, in theory, could curb.

At least three suicides have occurred at the bridge this year alone, Inquisitr reports. While officials are accepting with the idea to erect a barricade, the project is estimated to cost upward of $2.5 million in order to produce an architecturally sound barrier. This has the community split, with some suggesting the effort will fall short and do little to prevent deaths.

"I don't particularly feel that throwing money at an issue necessarily solves it, and altering the bridge because of a few people who want to end their life seems pointless," said Les Anderson, a magician who voiced his opinion on the group's Facebook page. "You're not going to stop someone who wants to end their own life."

A total of 17 people have taken their lives at the bridge within the last decade. There's no conclusive data for suicides since the bridge's opening in 1926. One effort to stop suicides include signs on the bridge with the telephone number of a suicide prevention hotline, which were placed there last September, an initiative by suicide-prevention nonprofit Lines For Life.

Those with a more grim outlook on the situation may not be too far off. A 2010 study showed that rates of suicide at the Bloor Street Viaduct in Toronto changed little even after the city implemented a $5.5 million barrier, the examiner reported. Studies have also shown that suicide rates overall do not change among cities with barricaded bridges and cities without.

Supporters of the barricade, however, note a 1978 study by psychologist Richard Seiden of the University of California, Berkeley. It found that less than 10 percent of the 500 people deterred from jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge eventually killed themselves. Garrett Glasgow, a political science professor at UC Santa Barbara, contended the findings, noting that most suicides on the Golden Gate Bridge were stopped by human intervention, a much better means of prevention than barriers alone.

Kahn said the barrier wasn't just about preventing suicides, but preventing the trauma it causes to the community. Many drivers and pedestrians are unwilling witnesses to those who jump off the bridge.

"There's a reason we have flesh," Kenneth Kahn said. "We're not supposed to see this stuff."

As the debate continues, authorities are struggling wieghing the options, with many generally in favor of a mode of prevention, but noting that there is no foreseeable means to do it.

"We certainly think of it as a high priority," City Commissioner Steve Novick said. "But there's a whole mess of competing priorities and not much money."

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.