Puerto Rican Gov. Alejandro García Padilla announced on Monday that the island nation cannot pay its $72 billion debt. He called on citizens to tighten their belts, on creditors to take some losses and on the U.S. government to change laws governing the territory he represents. Puerto Rico’s biggest problems, from debt, to the economy, to staggering out migration are interlinked. They’re also exacerbated by some bizarre quirks in U.S. law, like WWI-era shipping rules and the bluntness of the federal minimum wage. It has taken the present crisis to get even a modicum of attention from the rest of the U.S.

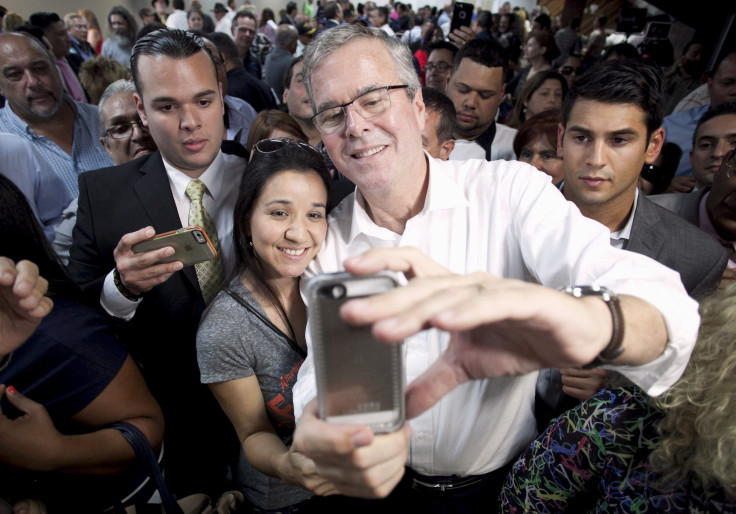

Puerto Rico is a blind spot in American democracy. Like fellow non-state Washington, D.C., it has no representatives in Congress. Like fellow U.S. territories, its residents can’t even vote in presidential elections. Puerto Rico, thus, produces exactly zero electoral votes that we can see on a map in red and blue. But the Boricua vote extends far beyond the island, most significantly to Florida, a battleground state with 29 electoral votes. Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush knows the hidden electoral importance of Puerto Rico better than anyone. He is the first (and so far only; Clinton says she’s going later this year) 2016 presidential hopeful to visit the island this year. Why court the favor of 3.5 million people on an island who can’t elect you? Answer: for their 5.5 million mainland residents who can.

“It is time for us to ask for concerted actions from Washington, in one voice, now. Action wherein changes can finally be made to Chapter 9, so that Puerto Rico can count on the same protections as other jurisdictions,” Gov. García said in his prepared remarks yesterday.

Gov. García told his constituents that the Puerto Rican debt crisis “is not about politics [it] is about math.” While that may have some truth on the domestic side, his speech delivered an overt political message to Washington.

Puerto Rico may not seem like a political player on paper, but rest assured that it’s debt crisis will impact the 2016 election. In addition to its electoral importance (more about that below), it’s also a stage for some of the country’s most pressing issues. Take the minimum wage, which some Democrats say they want to raise to $15/hr. While the minimum wage can help redress rising inequality, it’s a blunt instrument that ignores geography. Puerto Rico is a classic example where a minimum wage might not be as wise a living wage; something that takes local costs and economy into account. Puerto Ricans making minimum wage earn 77 percent of the average income, whereas mainlanders making the same amount (7.25) earn 26 percent, as WonkBlog pointed out yesterday.

More than serving as a case study, the Puerto Rican debt crisis is already creating its own major debates. Should Puerto Rico be allowed to file for bankruptcy? Will the federal government bail the island out? These questions are likely to make their way in front of presidential candidates as the 2016 race kicks into gear.

1) Westside Story To Southside Tampa: Demographics And Migration

When most Americans think of the Puerto Rican community, they’re thinking West Side Story. In the 20th century, plenty of Puerto Ricans made a new home in New York and other areas in the Northeast. Over time, a lot of those Newyoricans moved to Florida. Then a more significant migration happened. As Puerto Rico’s economy started to unravel in the 2000s, emigration increased. The unemployment rate was at 12 percent. By 2010, Boricuas were leaving the island at four times the rate they did in previous decades. Many of those migrants are moving to Florida. Aside from orange juice and swamps, the Sunshine State has a large service industry where displaced Puerto Ricans can get a fresh start.

"No question, the influx of Puerto Ricans has had an impact," Steve Schale, a democratic campaign strategist told Yahoo news last fall. "Until a few years ago, Central Florida was reliably Republican. No more."

Puerto Rican exodus from the island to the mainland is shifting effectively disenfranchised U.S. citizens from their electoral no-man's land to a hotly contested place in the race. Why does Jeb Bush care? Because Puerto Ricans lean Democrat, unlike their Cuban-American counterparts. Around one million Puerto Ricans now live in Florida. Cuban-Americans number around 1.3 million, but they’re also becoming more liberal, especially among the younger generations. In Florida, the Latino vote is up for grabs. While Gov. García’s constituents might not be able to elicit policy pledges from candidates directly, they might be able to pressure White House hopefuls into making some kind of promise to lock down the Boricua vote on the mainland.

2) Much Ado About Bankruptcy

Puerto Rico can’t file for bankruptcy the same way that an individual, a company or U.S. municipality can. Bankruptcy is the orderly process of picking the bones from a financial entity that is basically screwed. Borrowers get a clean slate: no more debt payments and a possibility to rebuild their credit in the future. They’re also left with the bare “bones” relevant to the entity. Individuals, for example, keep their primary residence. Lenders cut their losses, getting some of their money back and making sure that other debtors don’t get more than their fair share. Without bankruptcy, lenders are incentivised to squeeze every last drop out of Puerto Rico’s coffers.

That doesn’t mean the island hasn’t been trying to file for bankruptcy. Puerto Rico passed a “recovery act” that aimed to allow some of its most troubled institutions to go bankrupt. A U.S. court said that the law was invalid and contradicted federal law. Only Congress has the ability to change the rules and allow Puerto Rico or any other territory to be eligible for official bankruptcy, called Chapter 9. The Puerto Rico Chapter 9 Uniformity Act of 2015 would allow some elements of the island’s public sector institutions to use this financial tool.

Opponents of the bill say that Puerto Rico’s debts were accrued while Chapter 9 was not an option. Therefore, any such bill would violate the rights of lenders. There seem to be two other alternatives. One, let Puerto Rico default on payments. Two, a partial federal bailout, something that the White House says it’s not even contemplating.

Who will save the island? Jeb Bush has already endorsed Puerto Rico’s pro-statehood movement (which might technically allow for Chapter 9). But then again, he’s one of the few candidates who has paid much attention, at least publicly, to their plight.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.