With a gun in hand, Colonel Victor Revoredo and his team watched a small house where one of the most wanted criminals in Trujillo, the epicenter of extortion in northern Peru, could be hiding.

"This is where Cortadedos (Finger Cutter) lives," whispered the head of an anti-extortion task force trying to clean up the city of just over a million inhabitants, the third largest in the Andean country.

It was in Trujillo in 2006 that gangs began to impose their violent extortion methods, demanding a "tax" on the transport sector, according to former security minister Ricardo Valdes.

Today, "racketeering has become widespread and the main source of income for gangs," he told AFP.

It is not just wealthy individuals and large companies that are targeted -- small traders in poorer districts, where many people work in the informal economy, also fall prey to criminals.

Revoredo described it as a "crime pandemic."

Shops, motorcycle taxi drivers and schools are all victims of extortion.

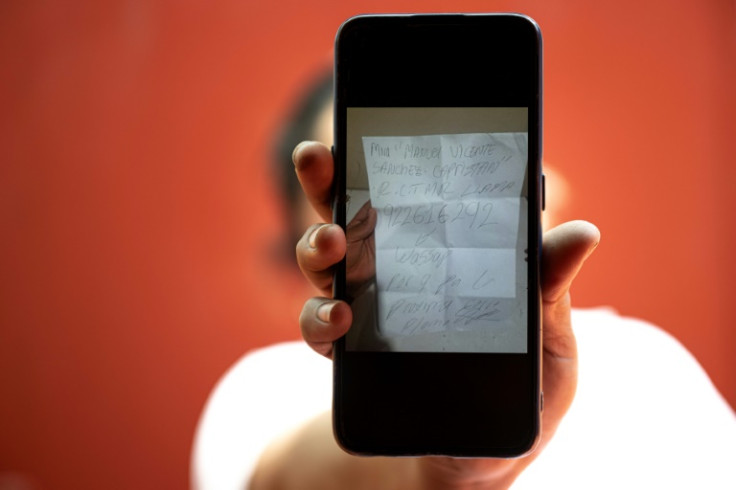

"If you don't want blood to flow, pay 20,000 soles" (a little over $5,000), reads a threatening message shared by the father of a recently murdered businessman.

If payment is not made quickly, the gangs begin intimidating their victims by shooting at their houses or businesses, according to other anonymous testimonies collected by AFP.

Revoredo said that a price of $40,000 had been put on his head by several criminal organizations, including the two main ones operating in the city, Los Pulpos and La Jauria.

Police have stepped up their hunt for "Cortadedos," real name Jean Piero Garcia, a member of Los Pulpos, after the kidnapping in August of a businessman's son who had six fingers mutilated to pressure his father to pay a $3 million ransom.

When police entered the modest house in Trujillo's El Porvenir neighborhood, the suspect had already fled. He was captured two days later in the same neighborhood.

"Crime is not defeating us. We're not triumphant. We still have a lot to do," Revoredo said.

Los Pulpos and La Jauria impose their brands and reigns of terror with stickers on the outsides of homes and vehicles bearing the image of an octopus or a yellow puma, reflecting their names.

"Life is short, death is endless," says the Los Pulpos sticker.

Peru's small businesses lose an estimated $1.6 billion a year to racketeering, according to an association representing them.

While extortion is a problem across Latin America, it recently took on alarming proportions in the Peruvian capital with the murder of three bus drivers.

The government declared a state of emergency in parts of the city of about 10 million and deployed the military to boost security after transport workers went on strike in September.

Fresh protest marches were held on Wednesday, prompting an expression of "solidarity" from President Dina Boluarte.

"We will not stop fighting crime with intelligence action and police operations," she said.

Police say more than 14,000 reports of extortion have been recorded across the country since January.

Organized crime has grown considerably in recent years in Peru due to Venezuela's migration crisis, firearms trafficking and the arrival of powerful gangs such as the Venezuelan-based transnational crime group "Tren de Aragua," the government recently acknowledged.

In April, teacher Diomedes Sanchez received threats: pay $2,500 or the small school he opened in Trujillo 20 years ago would be blown up.

When he refused, a bomb was thrown outside the school.

"We had to suspend classes for a week," the 50-year-old told AFP. "We can no longer work in peace."