When Sinaloa Cartel leader Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán Loera was captured by Mexican authorities in February 2014, U.S. law enforcement cheered a rare victory in the fight against drug trafficking and organized crime. That same month, the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a report along with the 288 Sinaloa Cartel companies on its “Kingpin Act” blacklist, companies whose assets in the U.S. had been frozen as early as 2007, companies who were American companies were prohibited from doing business with.

After Guzmán escaped on July 11th, 2015, Univision anchor Jorge Ramos called his prison cell and escape tunnel “a monument to corruption .” Prison officials had never moved him among the prison’s hundreds of cells, enabling El Chapo’s associates to tunnel to him from a construction site overseen by one of companies. A gaping hole in the floor would have easily been discovered by guards who weren’t on the take. Seven guards have been arrested and charged in the escape and officials acknowledged that it was an inside job. Yet impunity for El Chapo and cooperation with government officials extends far behind the bars of his former cage.

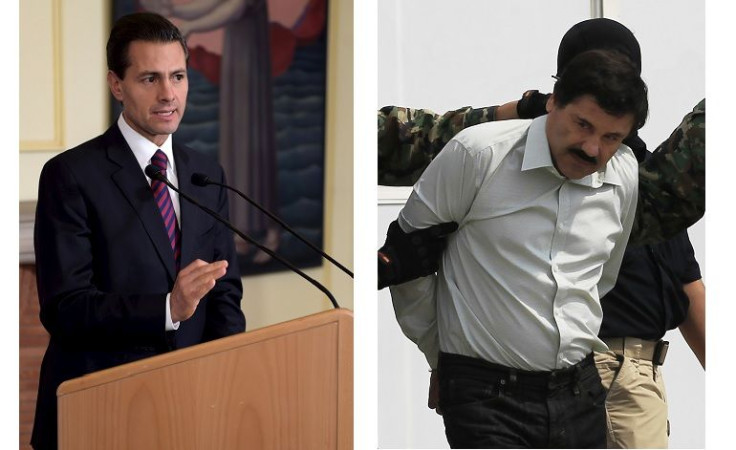

At least 14 of those Sinaloa Cartel companies have worked directly with the current Mexican government, the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, according to Univision and El Universal . The latter described government Sinaloa Cartel contracts as “working with the enemy,” and showed that Peña Nieto’s government did business with them even after being flagged by the U.S. Treasury . Sinaloa Cartel businesses not only profited from government contracts, but used their legitimacy to help launder drug trafficking money. In at least some of those cases, contracts were awarded years after being added to the “Kingpin Act” list.

In one example cited by El Universal, a nursery called La Estancia Infantil Niño Feliz was designated by the OFAC in 2007. Why had the Treasury given the company a red flag? Because the company was founded by a daughter of a Sinaloa Cartel capo, María Teresa Zambada Niebla. Before making it on the Treasury blacklist, La Estancia won childcare contracts from the government in 2001 and 2004. By 2009, the Mexican government acknowledged that the company was being investigated. Yet the contracts continued until at least last year, and up to 8 million pesos per year passed through the hands of the cartel-owned business.

Most of the Sinaloa Cartel’s suspected holdings are in real estate and so-called “trading companies.” Many are suspected to be money laundering fronts for drug trafficking operations. Some are gas stations, who sell gas from the state oil company, Pemex. Other’s are construction companies, trucking companies and furniture stores. Working with the government, they’re a living, breathing monument to corruption across the country.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.