Jaime Ballesteros sat down in the chemistry lab where he was working with a team of fellow students and faculty to analyze the chemical composition of one of the world’s first photographs. Like the rest of the researchers, he was focused on two questions: How did this photograph occur? What was the chemistry behind it?

It was summer of 2011, and he was a sophomore at Drew University. He had a few minutes after lunch to catch up on the news.

By all accounts Ballesteros had overcome the odds. He was 11 when his father brought him to the U.S. from the Philippines legally on a visa, which soon expired. He’d lived in the U.S. illegally ever since, but managed with the help of a mentor and the force of his wits to make it into college.

He had landed the perfect summer job, something that combined his art history major and chemistry minor, a positive step on path to what he figured would be a career in art preservation or gallery work.

But that day in the laboratory Ballesteros opened up an article in the New York Times that would change his trajectory.

The article was “My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant,” the second coming-out of Pulitzer-prize-winning Filipino journalist José Antonio Vargas, who had found it easier to tell his family that he was gay than admit to his colleagues that he was an immigrant who lived in the country illegally.

Vargas, Ballesteros and millions of other immigrants who grew up in the U.S. without legal permission are known as Dreamers, a moniker from the “Dream Act,” a bill that, if it had been passed by congress, would have given undocumented youth legal status and a pathway to citizenship.

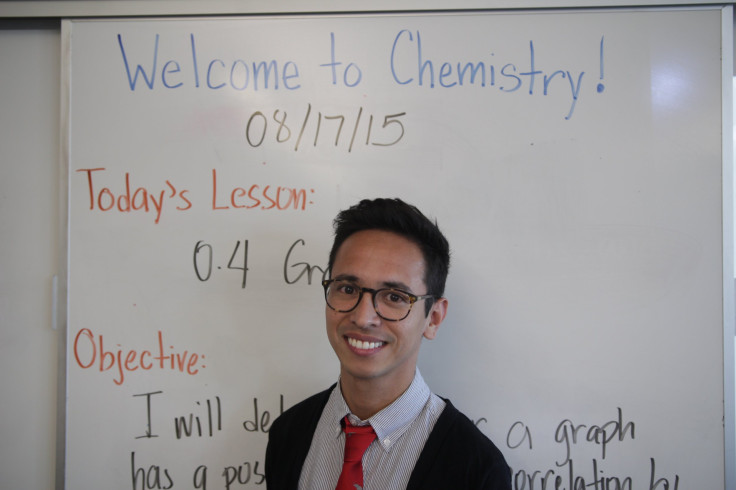

“I read that article and I remember crying in the lab and I felt like he was telling my story,” Ballesteros tells me in September of 2015, in a high school chemistry lab in Los Angeles. “As a gay Filipino American I really felt like he was really speaking my truth. It really resonated with me.”

The chemistry student is now a chemistry teacher, starting his second year at Animo College Preparatory Academy, in Watts, Los Angeles, where he is a corps member at Teach For America. That’s given him an opportunity to tell his own truth, and translate his experiences constructively.

“I feel that Teach for America serves as a platform for us to tell our stories and make a difference with our stories,” he says.

Last summer, that platform brought Ballesteros to the White House where he was honored along with five other TFA members as “Agents of Change.”

The ceremony was overseen by Domestic Policy Council Director Cecilia Muñoz and immigration activist and Colombiana actress Diane Guerrero (Maritza Ramos in “Orange is the New Black”, Lina in “Jane the Virgin”). The event got tons of coverage.

All of these teachers are, to borrow a term frowned upon by AP style, “illegal immigrants." Overcoming the stigma of their legal status, they've gaining recognition from the maintream and become leaders in the youth struggle for immigration reform.

None of the teachers would have been able to work for TFA without Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which was implemented by the White House in 2012. DACA is Dream Act lite, a temporary status that’s neither “undocumented” nor “legal.” Ballesteros and other immigrant youth in this situation refer to themselves as “DACAmented.”

How do DACAmented youth make a difference in a schoolhouse? To learn more, the Latin Times spoke with Ballesteros and one of his DACAmented colleagues about the daily grind of being a TFA corps member.

A Dreamer’s Approach to Struggling Students

Rosario Quiroz Villarreal Teaches 4th graders at Alvarez Elementary in the Rio Grande Valley, in Texas. Like Ballesteros, she is a DACAmented TFA Corps Member and an Agent of Change honoree. She is not stranger to struggle.

“I was raised with a lot of stigma around being undocumented. That was such a huge part of my experience,” she tells me over the phone.

Quiroz Villarreal tells me about her students, and the unique challenges they face.

“How do I explain? On the first day of school, you see kids come in and they don’t have supplies. All of our kids get free lunch. For some of them it’s the first meal of the day,” she says.

Her students’ parents are hard to get on the phone. They’re often at work, or their phones are disconnected. Many are immigrants who don’t speak English, making them shy to show up to parent conferences or check in before they learn that Quiroz Villarreal is Mexican.

Back at Ballesteros' high school in Watts, teachers compete with normal challenges -- hormones, short attention spans, cell phones and growing pains -- and extraordinary ones.

“A lot of my students live at the Jordan Downs, which is a housing project just down the street,” Ballesteros says.

The two-storied pink apartment blocks of the Jordan Downs stand out against Watts’ townhouses. Outside, clotheslines run between the rows, each of which is marked by three-foot high black numerals against the pink paint, like the roof of a bus or a police cruiser.

Inside, Ballesteros tells me, the apartments are often overpacked.

“The night before they just didn't get any sleep because some of them don't have bed to sleep on because they have a lot of family members that they live with,” he says. “I have some students who come into my classroom first thing in the morning with their head down.”

Other times, they have trouble fulfilling their teenage responsibilities because they’re already burdened with the demands of adult life.

“When they come home they look after their family members; their little brothers, their little cousins. They make sure that they are able to tutor them and to feed them because a lot of the time their parents are absent from their lives,” he says.

Ballesteros uses his personal scars from adversity to connect with his marginalized students. From the outside, those connections are intangible.

“I try not to appeal only to my students that are undocumented. I try to make this into a universal struggle in which all my students can relate to in which this was my challenge, but I was able to overcome this challenge because I asked someone for help -- that was a first step -- and I persevered,” he says.

He sometimes doubts the tangible outcomes of those relationships. He can’t find his students a place to sleep or give their parents green cards.

Cream Of The Crop

DACAmented graduates like Ballesteros and Quiroz Villarreal are key to building diversity in Teach For America. In 2013, the first year that DACA was available, two eligible immigrants served in the corp. In 2015, there are 100.

DACA Corps Member Support Director Viridiana Carrizales says that that diversity in its corps is essential to helping students succeed.

“[Corps members] who share the backgrounds of their students,” Carrizales argues, “bring with them experiences and perspectives that help them build strong relationships [...] and serve as role models.”

Of the 11.2 million immigrants in the country illegally, more than 1 million are under 18. TFA believes that teachers who grew up in households have an edge on meeting their needs.

“This is why we recruit, train, and develop our nation’s emerging leaders, including those with DACA status, to focus their talents and passion on expanding educational opportunities in our most underserved communities,” Carrizales says in an email.

It’s come full circle for Ballesteros, who has been able to directly help the handful of students in his class who are undocumented. It took a valiant mentor to help him get to college, and the Vargas article to have him come out as an immigrant in the country illegally.

"One of my students raised her hand and she asked me 'Mister, did you apply for the FAFSA,'” he recalled, referring to the nationwide financial aid form that enables incoming college students to apply for federal grants and loans. “I told her, 'No, because I'm undocumented.' My students know that I'm undocumented because I tell them my story on the first day of school."

TFA’s push for diversity is increasingly focused on Latinos, who are underrepresented in the teaching profession. This month, the organization announced its new goal to recruit 2,400 Latino undergraduates over the next three years.

That’s ambitious, considering the fact that only 4,300 Latinos have served in TFA since 1990. In the past two years, Dreamers have constituted a significant percentage of those Latino recruits.

Clearly, TFA selects them for their experience overcoming adversity. It is also possible that they’re more likely to apply, and more committed to social justice.

“I remember -- when I was graduating and it was during the recession -- some people at my college wanting to apply to TFA as a placeholder for two years,” she says. “If ultimately your goal is not to do something with education or social justice then you need to think twice,” and ask yourself “What can I bring to the table?”

Ballesteros says that he felt more compelled because of his background.

“I was friends with a lot of theater and art and art history majors. I feel like my friends from college are definitely aware of social justice issues but aren't necessarily working directly to help solve those issues.”

What Should America Do With Dreamers In 2017?

In 2017, DACAmented students like Ballesteros will either get deported, be eligible for citizenship or continue one in their precarious legal purgatory: Their future depends on who wins the 2016 elections. Presidential candidates on both sides of the aisle support Dreamers.

Democrats in the race all say that they would continue or expand DACA (at least the parts of it that aren’t struck down by courts). Frontrunners Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have pledged to maintain Barack Obama’s executive actions and push for a pathway to citizenship.

Clinton is more skeptical about TFA.

“There was an argument for Teach for America, but I think we’ve learned a lot about how difficult it is for people with 6 to 8 weeks’ training to manage a classroom, to be able to really teach in a way that inspires and produces results,” Clinton at National Education Association “town hall” in October, proposing her own alternative service initiative.

Former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley disagrees. His own daughter is a TFA corps alum who is still teaching in her placement school in Baltimore. He’s particularly enthusiastic about the intersection of civil service programs like TFA, and immigrants, whom he dubs “new americans.”

“Under my immigration plan, I would grant deferred action to the greatest number of people possible. This will ensure that all those who receive deferred action are eligible for service opportunities,” O’Malley told the Latin Times in an email. “National service helps build community and heal our democracy.”

O’Malley has combined immigration and national service into his presidential platform.

“Part of my national service plan is making service an aspiration and core part of citizenship. I would welcome and encourage the efforts of New Americans to contribute to their country,” he says.

Many Republican candidates also support Dreamers in theory, and see TFA as an attractive alternative to government education reform programs.

“You’re an inspiration to us because in you we see all that the future of our country can be,” New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie said when he passed pro-Dreamer legislation in 2013.

Then there’s Carly Fiorina, the former HP CEO and current Republican presidential candidate. She has never held elected office but said in the past that she supports the Dream Act. Fiorina also supports TFA.

"I've been a participant in a great program called Teach For America over the years. Teach For America recruits young people to be teachers in very troubled neighborhoods,” Fiorina said in September at an education summit in New Hampshire, adding that TFA supports a “meritocracy” that can combat the role of teacher unions.

Fiorina participated by donating Bay Area efforts from 2009-2012 (her campaign denied our request for comment on her involvement with TFA or her current view on DACAmented youth). According to TFA, those funds supported “efforts to recruit, train and place new teachers.”

Jeb Bush is the only Republican candidate who has unequivocally committed himself to preserving DACA, or, perhaps more importantly, offering some legal status to their parents.

If Deported

Many prominent Dreamers have patiently suffered their families being split apart. Take Diane Guerrero, the Colombian actress and U.S.-born citizen whose family was deported when she was a teenager, or Jose Antonio Vargas, the author who has remained separate from his mother in the Philippines.

They stayed. But other immigrant youth might prove to be more pragmatic. What would Ballesteros and Rosario Quiroz Villarreal do if they were deported?

“I'll have no problem getting another job in the Philippines if I did get deported. However, I consider the United States my home. I've chosen to build my life and my career in service of this country, and getting deported will be a huge heartbreak for me.”

Quiroz Villarreal is already considering attending graduate school in Europe. As a Columbia University graduate and a TFA corps member, her resume is ripe.

Too often, Dreamers are lumped in with other economic migrants and refugees, as if they don’t have any options. Here’s the reality: Dreamers are going to college and coming out are even better prepared for the global economy than their peers.

They’re often bilingual and always pretested to overcome adversity. Some have endured long separations from their families for reasons beyond their controls. DACAmented college graduates have learned to survive and even excel in a generation criticized for its sense of entitlement.

Will American citizens with access to the ballot allow them to stay in the country in 2017? Better yet, can they convince them to stay?

One way is to offer their families legal status, too. For Quiroz Villarreal and Ballesteros, DACA isn’t enough. Both have brothers that, like the writer Jose Antonio Vargas, didn’t qualify for technical reasons.

“I have DACA but he doesn't. And my parents are still undocumented,” say Quiroz Villarreal, who is one of the 40 percent DACAmented youth with a DAPA-eligible parent, according to the Center For American Progress, a pro-immigrant group.

DAPA, immigration reform lite, is currently frozen pending a lawsuit spearheaded by Texas and 22 other conservative states.

Back in the Ánimo Prep chemistry classroom, Ballesteros is focused on the students in front of him. He’s trying to make chemistry personal for these teens the way that immigration was personal for them.

“Today we're talking about pollution. I try to hammer in the fact that yes, they live in Watts, and yes they have a lot of challenges, and some of those are a result of environmental issues,” he says.

Most of his students haven’t been far from Watts, some have never been to the beaches just a few miles to the West, the gleaming shores of Venice, the ferris wheel of the Santa Monica pier. How do you get a challenged to teen to engage in the abstractions of science?

“We read an article that said that the residents of Watts have an average life expectancy that's 11 years less than the average life expectancy of someone who lives in Beverly Hills,” he says. “They don't know that the air that they're breathing in is actually worse than the air that they would breathe in another area.”

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.