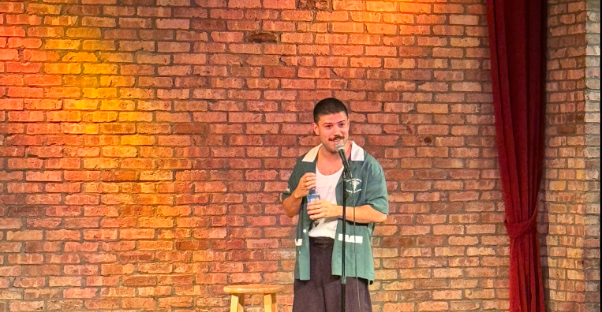

Angelo Colina's film school professor told him he was not good at writing dramatic scripts, but that he was funny and he should pursue comedy. So he did.

After leaving his native Venezuela and following a stint in Colombia, Colina arrived in the U.S., specifically in Salt Lake City. He started doing stand up in English, but quickly switched to Spanish. And it worked. As his audiences continued to grow, he focused on that line of work and undertook different projects, among them Español Please and now Gente Funny. Additionally, Colina has released his first special, Little Alone, a wordplay with the term solito in Spanish.

Speaking with The Latin Times, Colina went over his transition from comedy in English to Spanish, analyzed how the Latino cultural scene has changed since his arrival to the country and also described how within this community people from different nationalities can be different kinds of audiences, with their own behavior and sense of humor.

The following interview has been edited for extension and clarity purposes.

How did your career in comedy begin?

I was supposed to do a drama script for a class and my professor told me I sucked at drama. She said I should do comedy because I was really funny. She and I had a very similar sense of humor. So I did a comedy script and then I shot the short film and that kind of went viral. The experience was joyful, unlike drama. So i said i want to do this for the rest of my life.

How did you end up in the U.S. and how did you start there?

I first moved to Colombia and tried to do comedy there, but it was really hard to get any spots. Later I moved to Salt Lake City, so I had no other choice but to try in English. That was my only way because I didn't know anybody. There are a lot of Latinos in the city but there's not a sense of community.

I'm also a content creator so I posted everything online and it started reaching people. That's how I connected with Latino comedians all over the country and with people back home too. When they came touring here, I would open for them. And when it became more frequent I decided to move to New York.

Verdades latinas. pic.twitter.com/As2MGI2PQi

— Angelo Colina (@angelocolina) November 7, 2023

How was the switch to Spanish?

I was with another comedian and we thought about just doing a show because there were not even open mics here in Spanish to try out material. Because that's why you become a good comedian, by going on stage.

Luckily we already knew many international comedians. So after we opening for them we said 'alright, let's just start shows,' and we did. At the beginning maybe 25 people would come. But after the bulk of Covid passed we resumed and it grew quickly, we started getting like 800 people. It became successful because people didn't know it could be a thing.

How does the language influence your relationship with the audience?

I have had fewer setbacks than in English, when you often have to explain why you sound a certain way. This even happens to comedians who have been here for years. I noticed that in Spanish I don't need to explain who are Venezuelans. I don't need to explain myself, everybody knows who are the Venezuelans and what the country is going through. I am completely married to doing comedy in Spanish. Comedians who perform in English have started noticing me because fewer people do it and you can get more stage.

Have people suggested you do content in English as things have gotten bigger for you?

All the time. I still perform in English but for fun. Many times I get asked to open a show. I usually do better because I go to have a good time and oftentimes people can tell I'm enjoying myself. Spanish is harder for me but only because I feel I have to prove myself, but it's also better in the sense that it is more challenging and I love it way more.

How do audiences vary depending on their primary language?

Latinos are very polite. I don't know if it has to do with religion or what, but we're good at listening too. In English you can find people who can be racist to you or hecklers. At least I see it's more common. If someone would do that in Spanish maybe their friend would try to contain them or say 'don't embarrass me, don't make a scene.' I don't see that in American culture, maybe some would even be rooting for the heckler.

And how do they vary within the Latino community?

My main audiences are Colombian, Venezuelan and Mexican. But it changes depending on the city as well. In New York I do many jokes about Dominicans and Puerto Ricans because there are a lot of them there. Every time I use them they do well because everybody knows Dominicans here, but if I do it in Texas or Chicago they don't get them because they haven't met many. So I do them based on that and that's why I try to speak to people in the shows and after them to learn more.

Central Americans, for example, are extremely polite. There are many in Washington D.C. and they can listen to a story for 15 minutes just to wait for the punchline, and it might not even be that good, but they are a very well-behaved audience. In Miami or New York, in contrast, you have to be much more quick, go with hit after hit.

Based on your perception, have non-Latinos started to differentiate nationalities more?

It's a process that has certainly started more than people think. Of course, if you go to middle America many will mostly focus on Mexicans because it's the largest demographic and it's always been like that for them. But in the larger cities it's definitely happening. They tend to be more careful when addressing somebody, asking them where they come from specifically. There's a larger conversation than just assuming people are from one place.

It's mostly younger people and a lot of it has to do with reggaeton, whether people like it or not. They're trying to learn Spanish because they like Bad Bunny, Karol G and J Balvin. It's helped so much to give us value. And now many more people want to produce shows for us. It's happening and it's a great time for us.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.