When Libreria Barco de Papel first opened its doors in Queens in 2003, as a Spanish-language bookstore selling mostly children’s literature, it had plenty of adult peers across the East River: grand old Midtown institutions like Lectorum and Macondo, plus uptown upstarts like Calliope and Continental. “We’re the heirs to these great places which had been in the market for 40 or 50 years, but their business model got old quick,” says Ramon Caraballo, the bookstore’s Cuban-born owner. “Back then, it was ‘when I grow up, I want to be like Lectorum’. Now it’s, ‘when I grow up, I want to be like Amazon.’”

As many of its peers folded up shop, Barco de Papel grew up into the sort of place you can scoop up slim editions from creacionista poets or thick volumes of essays by Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, servicing both residents from the neighborhood -- working-class, immigrant Jackson Heights, which is about 56% Hispanic and 22% Asian, according to the latest census -- as well as intellectuals from the city and guests from Spain and Latin America who come to New York to read and discuss their work. The bookstore also hosts open mics and literary workshops, and the poetry collective Poetas en Nueva York calls Barco de Papel its home. Now, Caraballo is hoping to preserve his little hub of Hispanic literary heritage -- an essential “part of a vida digna” for community members, he says -- by transforming it into a non-profit, and has launched an online campaign to help fund the transformation.

Still, Caraballo and other booksellers catering to the Hispanic population, which makes up nearly a quarter of the city, have it comparatively easy. Just five or six blocks down Roosevelt Avenue, a host of other foreign-language bookstores clustered around the intersection of 74th Street, Broadway and Roosevelt Avenue, where five subway lines converge, have appealed to other immigrant communities in Jackson Heights and neighboring Elmhurst. Their numbers have dwindled; during a recent visit to the address listed for Mandarin-language bookstore Go Ba Wu, neighboring shop owners managed to communicate to me that it had closed. Others are just scraping by. Down the block, Urdu-language Mansoor Bookstore, which opened in 1990, started selling dresses four years ago in order to supplement revenues from Pakistani commercial novels and books about Islam. Store employees say over the past ten years, much of the area’s Urdu-speaking Pakistani and Indian population has been leaving the neighborhood. And fewer of their customers are young people. “Most young people have been here [in the United States] a long time and have no need for these books,” the manager told me. “They read English.”

The Bangladeshi presence in Elmhurst and Jackson Heights, conversely, has been growing over the past two decades, and with it, the promotion of Bangla-language literature and culture. The language is singularly important to Bangladeshi identity -- its movement for independence from Pakistan arose in large part in reaction to a 1948 law making Urdu the sole national language -- and since 1992, the Muktadhara Foundation has coordinated celebrations on Feb. 21st of what UNESCO calls “International Mother Language Day” and Bangladesh celebrates as a national holiday. In front of the UN headquarters, the Foundation builds a replica of the Shaheed Minar monument in Dhaka, which commemorates the pro-independence activists killed by Pakistani police during a Feb. 21, 1952 Bengali Language Movement protest.

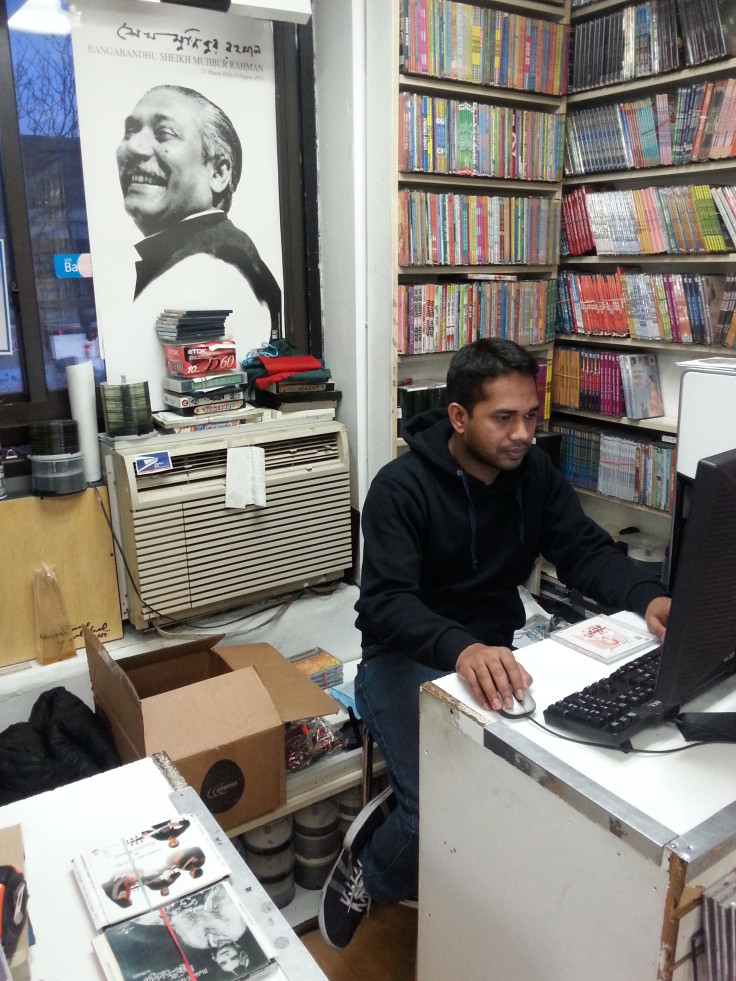

The Foundation’s current president, Bishwajit Saha, also runs Muktadhara Bookstore on 74th Street in Jackson Heights, across the street from the subway junction. Its shelves are packed with Bengali movies and music. But 24-year-old employee Shahriar Arif says the books – the memoirs of independence leader Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Humayun Ahmed’s novels, Nobel winner Rabindranath Tagor’s poetry – are the biggest sellers.“You can get DVDs and CDs online, but Kindle doesn’t sell books in Bengali,” he grins.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.