On the streets of a Bogota neighborhood where a businessman was killed for refusing to pay protection money, retired soldiers sporting weapons and camouflage gear keep a watchful eye on every movement.

Similar "self-defense" groups have sprung up all over Colombia's capital, a city of some eight million people that has experienced a surge in robberies and killings since the beginning of the year.

As fear has risen in step with crime, residents and business owners are taking matters into their own hands in a country with low levels of trust in the authorities.

"We are taking care of security. There are armed people here, but within the law. We are not illegal, we are military pensioners and the traders are paying us," one of the sentinels told AFP in Bogota's 7 de Agosto neighborhood, a bustle of autoparts shops.

Wearing ski masks and military-style boots, the men refused to give their names.

Some said they were paid by shop owners -- several of whom confirmed to AFP they were relying on hired guns to protect their lives and possessions.

Other patrolling guards claimed they work with the "Gaula" -- official law enforcement divisions created in the police and military to combat kidnapping and extortion -- a still all-too prevalent crime in Colombia as in other countries with a presence of drug gangs.

But Gaula officials told AFP the non-uniformed sentries have nothing to do with them.

"Civilians have no place" in the fight against extortion, insisted Colonel Cristian Caballero, commander of the Military Gaula in Bogota.

Shopkeepers in 7 de Agosto told AFP of the conditions in which one of their friends was killed in the first week of 2024.

Colleagues say he fell victim to the "Satanas" gang.

The criminals "come... they demand money, and if they (don't get it) they say: 'Kill them'," recounted one vendor who said he has taken to carrying a gun -- a privilege that under law is normally reserved for the security forces.

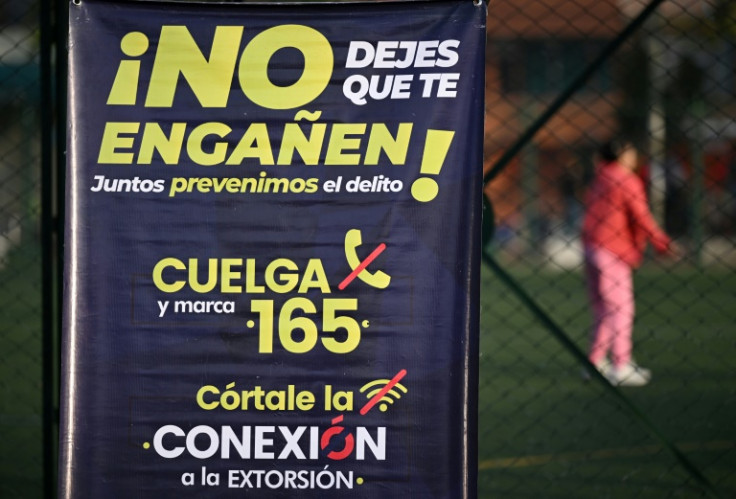

Large posters have gone up all over the neighborhood with the slogan: "I don't pay, I report!"

There is no official crime data for 2024, but the capital's mayor Carlos Galan recently said: "It is not a matter of perception... Bogota IS insecure."

Last month, the office of the ombudsman -- which monitors civil and human rights -- warned Bogota was the epicenter of a dispute between the Venezuela-headquartered Aragua Train criminal group and the Gulf Clan, Colombia's biggest drug cartel.

The South American country has seen violence persist despite a 2016 peace deal that led to the disarmament of the FARC guerrilla group.

In a civil conflict that has lasted six decades, FARC dissidents, other leftist guerrillas, rightwing paramilitaries and drug cartels continue fighting over territory and resources -- particularly in rural areas.

Bogota found itself in the eye of the storm of a cartel war in the 1970s and 80s with bombs and shootings commonplace, but has been comparatively peaceful and safe in recent years.

Many fear that is now changing.

Polling firm Invamer said in a recent report that insecurity is one Colombians' chief concerns.

And many are critical of President Gustavo Petro's negotiations with armed groups in his quest to finally achieve "total peace."

There have been calls for a change to gun laws and appeals for citizens to join "security fronts" or neighborhood watch groups.

One retired soldier told AFP he was recently asked to join a self-defense group in 7 de Agosto, but declined.

Hee was to be paid about $1,000 monthly to capture suspects and bring them to the authorities.

Another said he was being paid to call the cops on any suspicious-looking person in the neighborhood.

Bogota Metropolitan Police commander Jose Gualdron recently announced that hundreds of taxi drivers, motorcycle delivery agents and private security companies would be drawn into so-called "security fronts."

They will be unarmed, unpaid and tasked only with reporting suspicious activity.

For Isaac Morales, an expert at the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation, a Colombian thinktank, involving civilians in combating crime is a "desperate response" that could "open a pandora's box."

Indeed, many Bogotans shudder at the memory of so-called self-defense forces that were present in the city and elsewhere during a particularly bloody period of Colombia's recent past.

Initially created as protection forces against guerrillas, they later morphed into paramilitary groups that killed more than 7,100 people between 1980 and 2012, according to official data.

Defense Minister Ivan Velasquez insists the government does not support any undertaking that resembles any "form of self-defense" grouping.