A team of University of Alberta researchers who collected frozen plant specimens from the edge of a receding glacier high in the Canadian Arctic, wrote in recently published findings that they have been able to bring the frozen moss back to life. After taking the specimens - no more than a greenish tinge on the side of the Teardrop Glacier - back to the lab, grinding them up and placing them in soil, the moss was able to regenerate from parent material an estimated 400 years old. The Atlantic wrote that in total, the researchers were able to grow 11 cultures from seven specimens representing four distinct species.

The bryophytes - a category of plant including liverworts and hornworts and which can reproduce asexually, meaning they can go for long periods without light or water -- would have dated back to the Little Ice Age, a period from about 1550 to 1850, in which glaciers crept in to cover parts of the Northern Hemisphere. Since this period, the ice has begun to retreat, with increasing speed over the past ten years.

The lead author of the study, Catherine La Farge, told NPR in an interview that the bryophytes were able to regenerate in part because they were a plant type which would have routinely had to go through six months of winter darkness. Bryophytes are totipotent, meaning a single cell can "reprogram" itself to develop into different types of plants in order to best accommodate its environment.

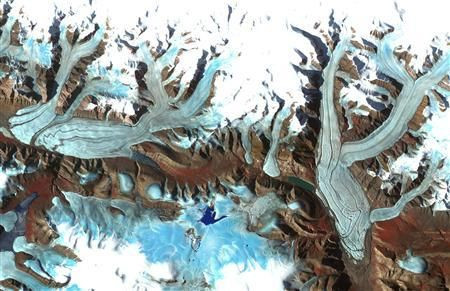

Deglaciated landscapes are known as excellent preservers of the ecosystems which once lived in them. The melting Teardrop Glacier where La Farge's team found the moss is especially high up in the Canadian Arctic and thus especially cold, meaning as it continues to recede with increasing speed, there could be potential discoveries of previously unknown and well-preserved life forms.

"It's basically like taking a blanket and pulling it back and seeing a little Ice Age community intact underneath this glacier," La Farge told NPR.

She added that she hoped the study would put bryophytes in the limelight, as their adaptability could have potentially far-reaching benefits for humans.

"Any kind of plant material that, say, would be sent to extraterrestrial areas, like if you wanted to try something on the moon or on Mars, definitely bryophytes would have a great potential because they are programmed to be able to dry out, desiccate totally. They are programmed in the Arctic species anyway to be able to be frozen for long periods of time."

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.